I

didn’t want the part. I didn’t care about the film. The story didn’t interest me. My agent, who also represented Tom Cruise, basically tortured me into at least meeting Tony Scott, saying he was one of the hottest directors in town and I could never afford to not meet with as many of them as possible, and also he was completely obsessed with me. Well, an agent doesn’t have to offer any other reasons when “the director is completely obsessed with you” comes out of their mouth.

I showed up at the audition because that’s what actors do when they’re asked to audition. I showed up looking the fool, or the goon. I wore oversize gonky Australian shorts in nausea green. I read the lines indifferently. And yet, amazingly, I was told I had the part. I felt more deflated than inflated. I had to get out of there.

I showed up at the audition because that’s what actors do when they’re asked to audition. I showed up looking the fool, or the goon. I wore oversize gonky Australian shorts in nausea green. I read the lines indifferently. And yet, amazingly, I was told I had the part. I felt more deflated than inflated. I had to get out of there.

The moment I got into the elevator, the director ran after me and slid his arm in to block the door. He blurted his truth in his chipper British accent: “I know that the script is insufficient, but it will get better, Val. Wait until you see these jets. They take your breath away.”

He then proceeded to imitate aircraft sounds and motions as if we were six years old and as if there were no one else in the hallway. “I know you’ve been told this before, I know you’re a serious actor, but you are perfect for this role. It’s as if they wrote it for you. It has to be you. It’s not the lead, but I’m going to make you feel like it is. And this kid we found, Tom Cruise, he has it, man, and you two together, and Kelly McGillis—you know her from Juilliard, she’s nine feet tall and utter perfection.”

He was a wrecking ball to my consciousness. I had never before been treated with such passion. I was so accustomed to giving passion, less familiar with receiving it.

Side note: I once flew to London when I couldn’t afford a ham sandwich to sit in a hotel room with a single videotape in hopes of hand-delivering it to Stanley Kubrick. Eventually I befriended one of his “people,” who told me after my forty-eighth phone call in one week, “I’m sorry, Val. He really liked the last video you did. I am not supposed to say this, but he’s really interested. In fact, we have stopped pre-production because of that last video. But he won’t see you. He just doesn’t work like that.”

Self-taping was new at the time, and Kubrick must have been enchanted with it. I got it. I was enchanted myself and had been shooting me and my friends since I could get my hands on a magical machine of my own. But Kubrick’s stubbornness sent me home, deflated.

Tony Scott’s British enthusiasm was the pick-me-up my ego craved. He was ferocious and hilarious. We both had penchants for fishermen’s vests. His was primly packed with pens, folded paper, and cigars, plus a monocle cinematographers use to examine the sun. Now video cameras adjust to let you film through the night, but it wasn’t like that back then.

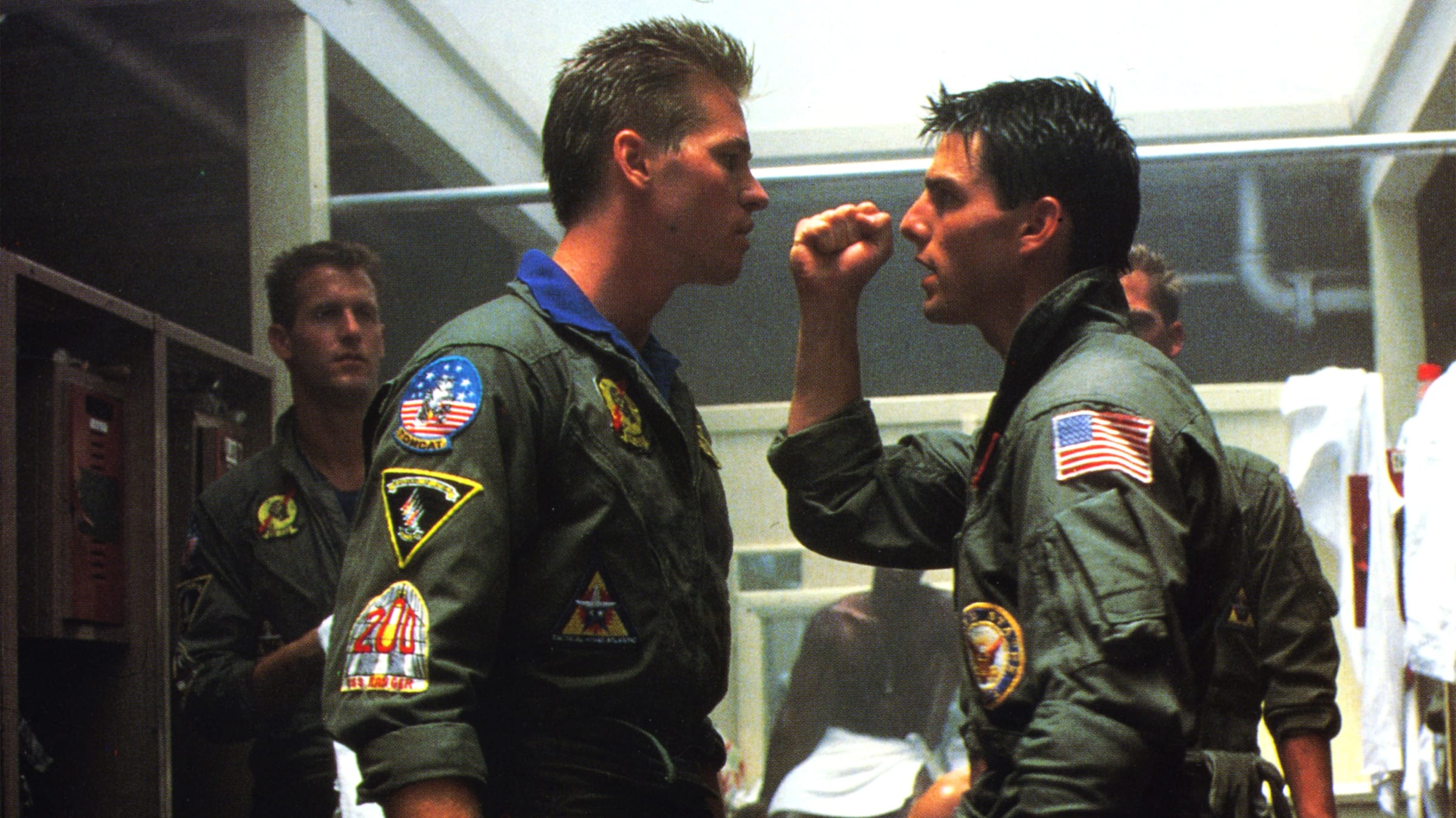

Tony loved the process, loved the energy of the set, loved the characters. Everything was fuel to Tony. Every time a jet took off, Tony swooned. I threw lines away. He would jump for joy. Ultimately, he overwhelmed my disdain for the project with pure unadulterated positivity. Every day he would exclaim, “This is incredible! This is beautiful! This is beyond belief. You guys are going to be kings.” Off set, the actors broke into two camps—mine and Tom’s, a reflection of the rivalry between our two characters. In the film, I was Iceman and Tom was Maverick. I commanded my camp because I had a tricked-out van.